Ink, Ears, and Ideas: The Power of Music Journaling on Paper

Music journaling looks, at first glance, like one more task stacked on top of an already crowded practice schedule. It can feel like “extra work” piled onto gigs, lessons, and recording sessions. But keeping a dedicated journal for your musical life is one of the most powerful ways to deepen your learning, sharpen your memory, and stay creatively grounded, and it works even better when you do it with paper, ink, and a pen you actually enjoy.

When you practice, listen to music, or have a sudden musical idea, those thoughts appear and disappear quickly. Your brain gives them a tiny parking space in short‑term or “working” memory, and then it clears that space for the next task. Cognitive psychologists describe this as the difference between working memory, which can only hold a small number of items for a brief time, and long‑term memory, which stores patterns and concepts for years. Writing is one of the most reliable ways to move material from that fragile short‑term buffer into more durable storage. When you physically write down a phrase you heard, a voicing you loved, or a production trick that caught your ear, you are telling your brain this matters; encode this. Studies on the “generation effect” and “self‑explanation” show that when learners restate ideas in their own words, they remember them far better than if they simply reread or highlight. Putting musical ideas into sentences or shorthand that make sense to you is essentially self‑explanation on paper, and your recall later is dramatically stronger.

The Start Up

Years ago, I began journaling guitar sounds and production techniques with no grand system, just scattered notes about tones, mic choices, and mix moves. Those early journals turned out to be priceless when it came time to make records or build cue lists on a deadline. In a session, you don’t always have time to experiment from scratch. Flipping back to a page where you described the exact fuzz–amp combination that cut through a dense mix, or the reverb–delay chain that made a solo sit perfectly, can save you hours. What surprised me was that after writing these observations by hand, I often didn’t even need to open the notebook. The act of writing, describing, and naming the sound had embedded it deeply enough that my brain treated it as a familiar tool rather than a half‑remembered accident.

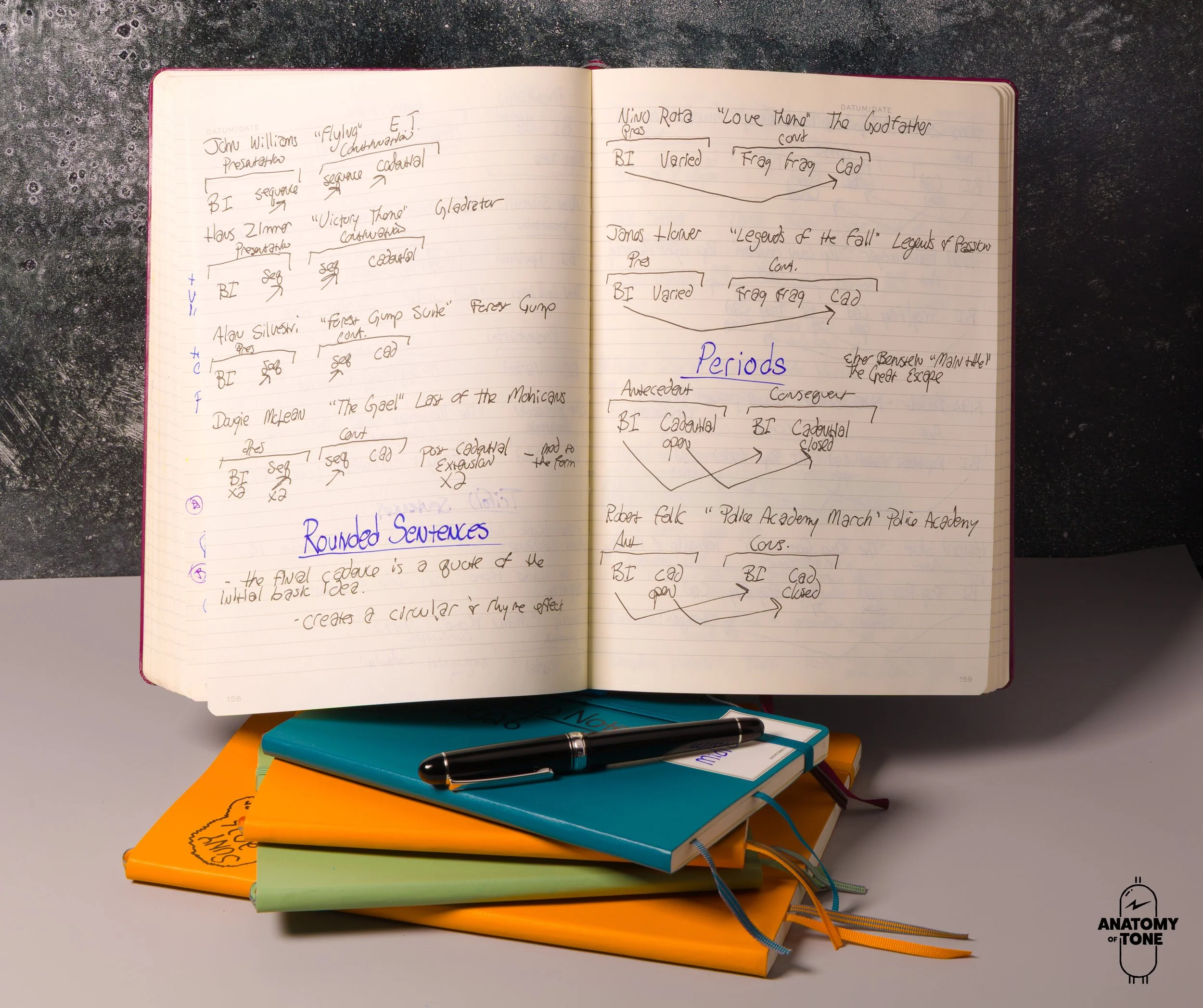

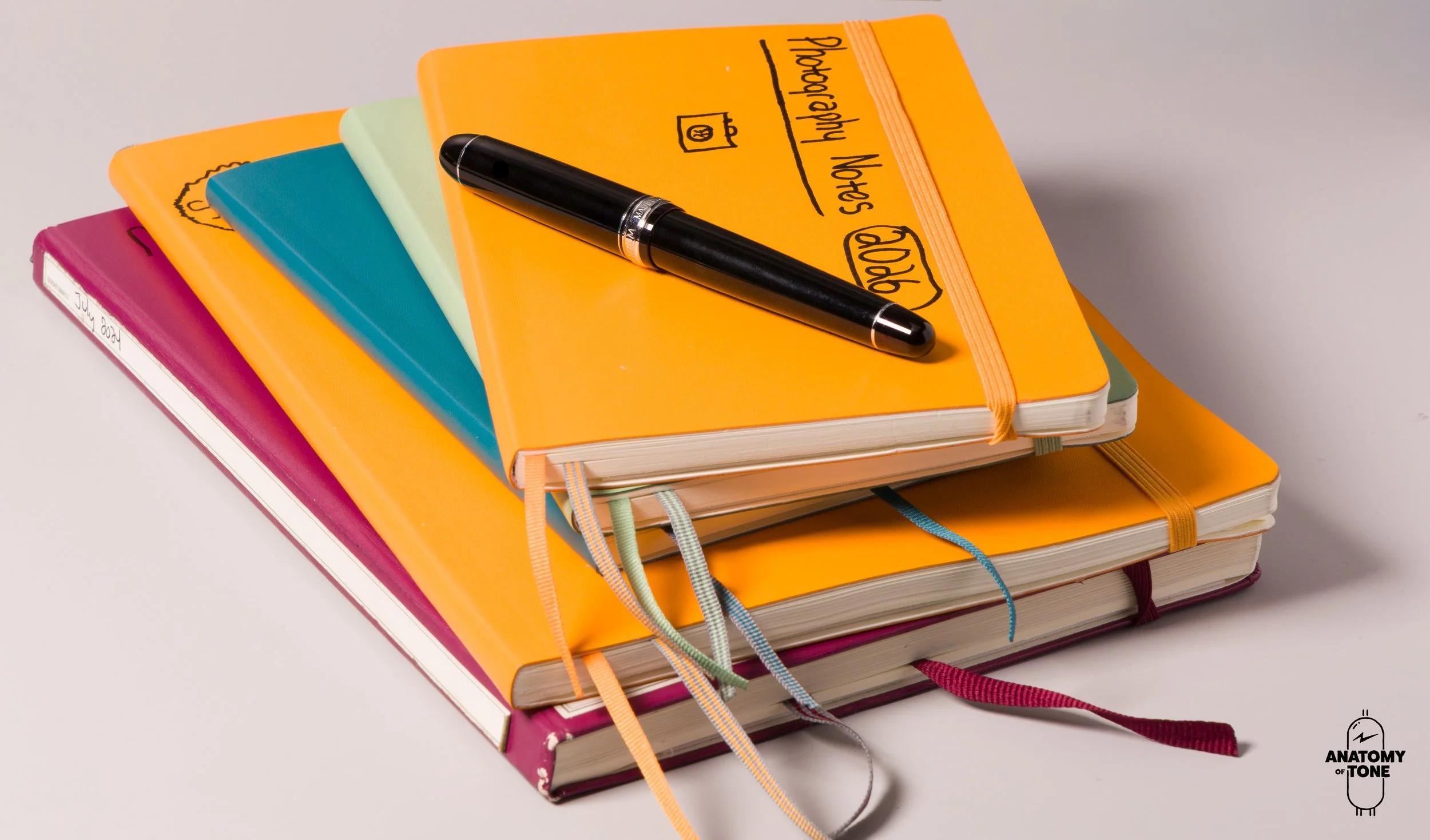

That is one of the quiet superpowers of journaling: it creates both an internal library in your memory and an external library on your shelf. If time passes and the details fade, the journal becomes your research archive. If the memory is still vivid, the page simply served as the original carving tool that cut the concept into your mind. Over time I began to separate my notes into dedicated journals: one for guitar sounds, one for synth patches, one for production and engineering, and one for composition and theory. This physical separation reinforces mental categories, which cognitive science calls “contextual encoding.” Your brain learns to associate each notebook with a specific mode of thinking, making it easier to retrieve the right ideas when you pick up that particular book.

My own path into serious music journaling grew out of a desire to fill in gaps. I became a professional session musician and toured widely without going to college, thanks to money issues and a chaotic home life. I learned a great deal on my own, but I could feel the empty spaces—concepts I’d heard of but never mastered, harmonic languages I loved but couldn’t yet speak. As my interest shifted from straight rock and blues into 20th‑century harmony and classical‑influenced film music, journaling became the scaffold I used to climb into that new sound world. Scores and soundtracks by Jerry Goldsmith and Bernard Herrmann, the eerie writing in The Twilight Zone, the original Planet of the Apes soundtrack—these became case studies in my notebooks. I would copy a few bars, sketch a contour, or describe the harmonic move in words I understood, not in abstract theory jargon.

In Your Words

This habit of translating material into your own language is another core principle supported by learning research. When you summarize, you are not just copying; you are reconceptualizing. Neurons that fire together wire together, and by tying a musical idea to your own phrasing, memories, and emotional reactions, you recruit far more of your brain’s networks than you do by passively reading a score or listening once. I took extensive notes on harmony books, then annotated those notes, then summarized the annotations. That might sound obsessive, but each pass deepened my understanding and also clarified what was still fuzzy. At that point, color coding entered the picture. Using different colors for harmony, form, orchestration, and listening notes let me see the structure of my learning at a glance. Cognitive studies on “distinctiveness” and visual encoding show that color cues help the brain separate similar information streams; a red underline or a blue box gives the eye—and the memory—a landmark to return to.

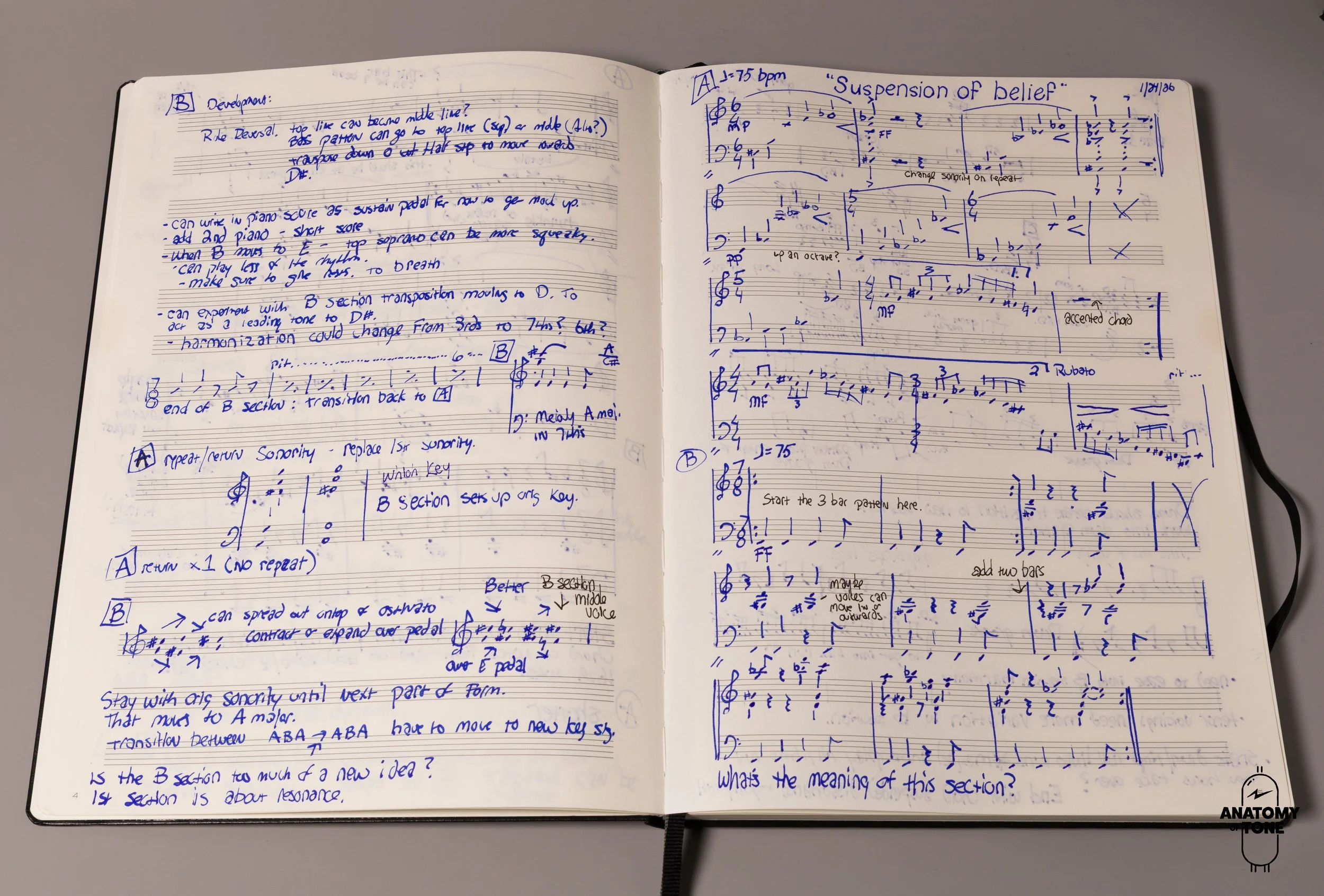

Music journaling is not only about copying down other people’s ideas; it is also a powerful tool for composing and problem‑solving. When I work on a piece, I “talk on paper” about what is working and what is not. I note where the melody stalls, where the harmony feels generic, where the orchestration muddies the gesture. This metacognitive reflection—the act of thinking about your own thinking—has been shown to improve learning and creativity because it switches you from automatic pilot into an observing, editing mindset. Writing on paper slows you down just enough to notice patterns and decisions you would otherwise rush past. It also creates a breadcrumb trail. I avoid loose sheets because they migrate, disappear, and sever that trail; instead, I tape stray sketches into a manuscript book. Even when I switch to digital notation or a DAW, these paper trails remind me how the piece evolved and why I made the choices I did.

You do not have to notate music to benefit from this approach. Lyricists, improvisers, beatmakers, and producers can all describe their processes in words: what emotion they were chasing, what sound they were referencing, what limitation sparked the best ideas. Journaling also becomes much more useful when you can find entries quickly. Early on, I ignored indexing and paid the price, flipping endlessly through pages to locate a voicing or idea I knew I had captured somewhere. Creating a simple index at the front or back of each notebook—dates, topics, page references—turns your journal into a searchable database. It mirrors how our digital tools work but keeps you away from the distractions that come with screens.

Future Forward or Backward

That brings us to the question of why paper at all, when digital devices are ubiquitous and powerful. On the surface, writing on a tablet or laptop might seem more efficient: everything is searchable, and it syncs across devices. Yet research comparing handwritten notes to typed notes finds consistent advantages for handwriting. When you type, you can often transcribe almost verbatim, which encourages shallow processing. With a pen, you simply cannot write as fast as someone talks or as fast as thoughts arise, so you are forced to compress, paraphrase, and prioritize. That deeper processing leads to better conceptual understanding and long‑term retention. On top of that, digital devices are distraction machines. Notifications, social media, emails, and the sheer presence of other apps pull your attention sideways. Focus is a limited resource, and music journaling works best when your mind can stay inside the musical problem instead of splitting itself between an idea and a timeline or inbox.

I am not anti‑digital; computers are essential tools for composing, recording, and publishing in the 21st century. But just because a device can do something does not mean it is the best tool for that job. Splitting tasks—using digital gear for recording, editing, and sharing, while reserving paper for reflection, planning, and conceptual work—can actually relieve stress. You always know where a given kind of thinking lives. When it is time for journaling, the phone goes away, the notebook opens, and your brain enters a quieter mode that is better suited to insight.

Choosing the right physical tools also matters more than many people realize. A journal you enjoy holding and looking at invites use. I like A4 books for music because the larger page accommodates manuscript paper and my not‑so‑great eyesight. For general note‑taking I prefer A5, and for truly portable “capture it before it vanishes” moments I use A6 or pocket‑sized Field Notes. Having a small notebook and pen on you at all times turns fleeting ideas into stored assets. When the paper is not pre‑printed with staves, I gravitate toward dotted pages rather than lined ones; the dot grid lets me draw a quick staff, sketch a piano layout, or outline a form diagram without fighting horizontal rules. Carrying everything in a simple bag with room for pens and journals makes it realistic to keep these tools with you rather than leaving them on a shelf.

Then there are the writing instruments themselves. Cheap pens and scratchy paper send a subtle message: this isn’t that important. You feel it in your hand every time the ink skips or the page feathers. Investing in better tools communicates the opposite message to your brain: this is significant, my work deserves quality, and this time with the notebook is special rather than disposable. That sense of ritual and respect changes how eager you are to sit down and write. High‑quality gel pens in a few colors make it easy to color‑code ideas: perhaps blue for harmonic analysis, green for production notes, red for “questions to research,” and black for general commentary. Smooth, non‑smearing highlighters let you mark themes without turning the page into a fluorescent blur.

A Pen Isn’t Just A Pen

Fountain pens occupy a special place in this toolkit. A fountain pen uses liquid ink fed through a nib by capillary action, allowing the pen to glide across the page with almost no pressure. Unlike ballpoints, which rely on friction and downward force, a good fountain pen turns writing into a delicate, almost musical gesture. Among the many fountain pen makers, Platinum stands out for its engineering and for a model that has become a favorite among musicians: the Platinum 3776. Named after the height of Mount Fuji in meters, the 3776 is a Japanese fountain pen with a steel nib, a well‑balanced body, and an ink‑sealing “Slip & Seal” cap mechanism that keeps the pen ready to write even after long pauses.

The “music nib” on some Platinum pens is specifically designed with musicians in mind. Traditionally, a music nib is broader and often has three tines instead of two, allowing it to lay down thicker, more expressive lines suitable for writing notation on staff paper. The line is wide enough that noteheads, stems, beams, and dynamics are easy to see, yet it remains precise enough for text. The generous ink flow makes writing feel almost like bowing a string rather than scratching graphite across paper, and that tactile pleasure creates a feedback loop: you want to write more because it feels good, and writing more deepens your learning. The 3776’s various nib options—ultra‑extra‑fine through broad and music—also let you choose how much line variation and feedback you want, much like choosing different picks or strings to match a particular instrument and style.

Ink color is another subtle but powerful dimension. Many musicians enjoy using a particular shade that contrasts clearly with the black of printed staves. A rich blue, for example, stands out against staff lines while being less aggressive than bright red. Color psychology research suggests that blue tones can support calm focus and creative thinking, while red can increase alertness and highlight warnings or key points. In practice, this means you might draft ideas in blue, reserve red for “fix this” comments, and use another color for structural markers or section headings. When you flip through an old journal, your eye instantly catches the red corrections, the green structural notes, or the gold highlighter around passages that mattered most.

Color coding as a broader strategy extends beyond ink choice. By assigning meanings to colors—say, yellow for ear‑training ideas, pink for rhythmic concepts, blue for harmony, orange for production—you create a visual indexing system running in parallel with your written index. Research on dual coding theory suggests that combining verbal and visual cues (such as color) enhances recall because the brain has multiple pathways to the same information. You are not just remembering “the page with the altered dominant lick”; you are also remembering “the line I highlighted in orange with the blue margin note.” Even simple practices like changing pen color when a topic changes or drawing boxes around terms with a contrasting gel pen increase the salience of that material.

Rock, Paper, Scissors

When you write with fountain pens, not all paper is created equal. A key term you’ll see is gsm, which stands for “grams per square meter” and indicates paper weight: higher gsm usually means a thicker, denser sheet. For fountain pens, what you are really chasing is a balance of weight, surface treatment, and sizing so that ink doesn’t feather outward or bleed through to the back of the page. In practice, most writers find that the 80–100 gsm range is a sweet spot for everyday journaling, thick enough to resist bleed-through while still keeping notebooks reasonably slim. Some specialty papers push the limits at lower weights: Tomoe River, for example, comes in ultra‑thin 52–68 gsm versions yet still resists bleedthrough and shows ink shading and sheen beautifully thanks to its coating. A simple rule you can share with readers is that well‑made 70–80 gsm paper can be fine for finer nibs and drier inks, while broader, wetter nibs really shine on 80–100 gsm and heavier, especially from brands that design specifically for fountain pen use.

For stationery and music manuscript work, the choice of brand matters just as much as the number on the package. Stationery paper from Clairefontaine and Rhodia (typically 80–90 gsm) is widely regarded as a benchmark: it is smooth, coated, and highly resistant to feathering and bleedthrough, making it ideal for letters, journaling, and everyday notes. Tomoe River offers a different experience with its whisper‑thin sheets that still keep ink on the surface and highlight color and sheen, while Midori MD, Midori Cotton, Life Noble, and modern options like Endless “Regalia,” Maruman Mnemosyne, and Stalogy balance smoothness with quicker dry times. Music manuscript paper is more challenging because very few off‑the‑shelf staff pads are truly optimized for fountain pens; even better‑than‑average options from major publishers can show some feathering or bleed with wet inks. Many fountain‑pen‑using musicians therefore choose high‑quality 80–90 gsm paper from brands like Clairefontaine, Rhodia, or Kokuyo Campus and print or rule their own staves, effectively combining proven fountain‑pen‑friendly paper with custom staff layouts.

I’ve had good luck with the Leuchtturm music stave books. There is some ghosting, but it’s not a deal breaker for me, since I’m using them to collect my thoughts, not hand them directly to musicians to play from. I’ve been using Leuchtturm journals for quite some time and really enjoy the overall quality and feel of their notebooks.

The Catch All

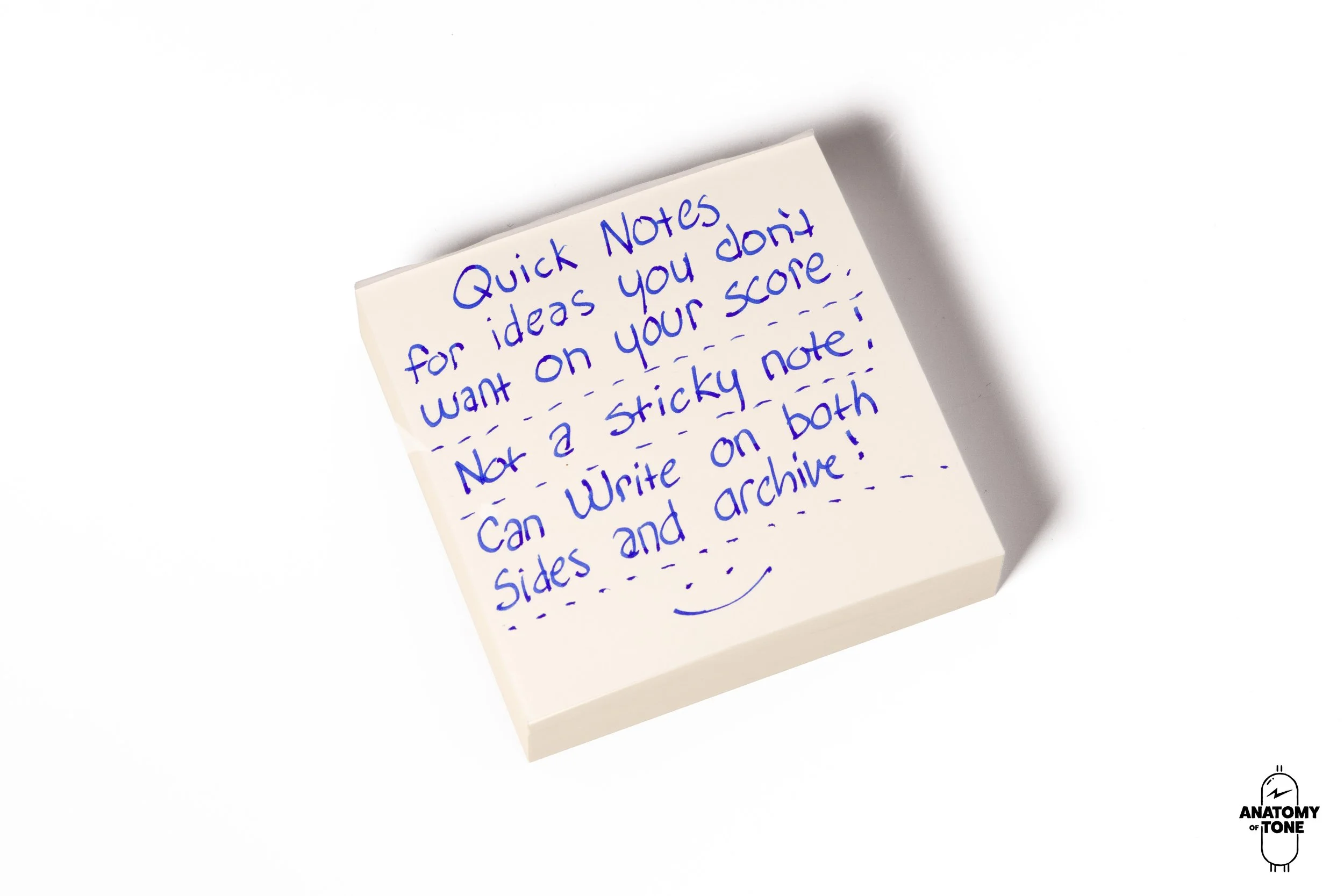

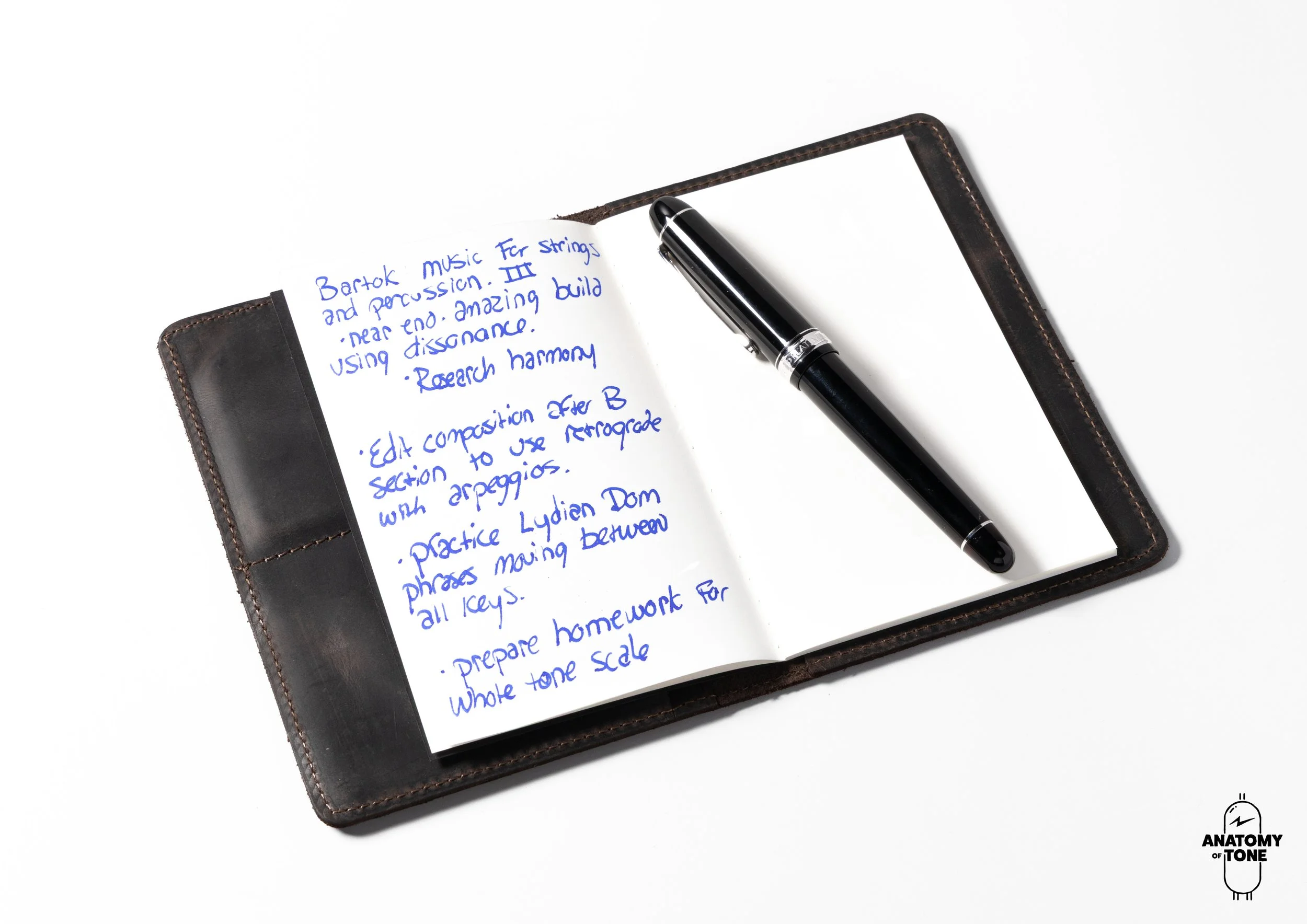

When I’m on the go, I even carry a small “catch‑all” journal with a handmade leather cover to keep it from getting destroyed. This little book is where every stray idea goes: if something pops into my head, I see a cool tip, or I need to jot down anything I don’t want to forget while I’m out and about, it goes into the catch‑all first, and then I transfer it into the appropriate journal later.

Over time, this has become a kind of mobile inbox for my brain. I don’t have to worry about which notebook something belongs in while I’m standing in line or riding the train; I just capture it once and sort it when I’m back in my workspace. That simple habit keeps me from losing half‑formed ideas, musical fragments, book recommendations, and all the other little sparks that would normally disappear if I told myself, “I’ll remember that later.”

Don’t Pass Me By

The journaling process itself benefits from multiple passes. The first pass is all about capture. You write down raw material during a lesson, a rehearsal, or a listening session, not worrying about organization. The second pass happens later the same day, when you refine the notes: rewriting messy bits, adding headings, boxing key terms, and deciding which lines deserve highlighting. A third pass, perhaps the next day, involves summarizing and reviewing. Cognitive research on spacing and retrieval practice shows that letting some forgetting occur before you revisit material strengthens the memory trace. If you review too soon, you are simply looking at something that is still warm in short‑term memory. If you wait a day, you are forced to reconstruct it, and that act of retrieval is what actually strengthens learning. Summarizing at that point in your own words—“today I learned that this progression creates this emotional effect; here is how Goldsmith used it; here is how I might adapt it”—ties everything together.

All of these practices do more than just improve your playing and writing; they also reduce stress. Musicians carry a huge cognitive load: repertoire to maintain, techniques to polish, deadlines to meet, and ideas we fear we will lose. A journal functions as an external brain. Once an idea is safely captured, your mind is free to relax, knowing it can return later. This lowers anxiety, which in turn improves your ability to focus and to enter that elusive flow state where creativity feels effortless. Music journaling, especially with tools that feel good in the hand and systems that make information easy to retrieve, becomes a form of mental hygiene. You are not just documenting your musical life; you are building a more resilient, organized, and inspired version of yourself, one page and one line of ink at a time.

Owning Your Words

We’ve slid into a moment that would have felt right at home in a mid‑century sci‑fi novel, except it’s not fiction anymore. Our phones, laptops, watches, cars, e‑readers, and even “smart” notebooks quietly generate a trail of data that says as much about us as the words we write. Governments and corporations now have the technical ability to monitor enormous streams of information at scale: who talks to whom, when, from where, on which device, and often what is being said. Social media posts, emails, cloud documents, search queries, location histories, and purchase records are routinely logged, analyzed, and cross‑referenced to build profiles, target ads, shape feeds, and, in some cases, flag so-called “risky” behavior or dissent. You don’t have to be a criminal, an activist, or a whistleblower to find yourself inside that net; simply existing online is enough to ensure that a detailed shadow version of your life is being assembled somewhere you’ll never see.

That’s the unsettling backdrop for anyone who cares about journaling, reflection, and the simple act of thinking on the page. When every word you type into a phone, tablet, or laptop has the potential to be synced, scanned, mined for “sentiment,” and stored indefinitely on someone else’s server, “private writing” becomes a more complicated phrase. Digital journaling can be both useful and secure if you choose your tools carefully and understand their settings, but the default stance of the modern web is collection, not forgetting. That’s one reason why analog writing—pen on paper, sitting at a desk, no account to log into—feels less like nostalgia and more like quiet resistance: a way to step outside the industrial data pipeline, even for a few pages at a time.

Two decades ago, it would seem like I’m being an alarmist, but the reality is right in front of our eyes. We’re living in a time when AI can remix our faces, voices, and words so convincingly that it’s getting harder and harder to tell what’s real and what’s synthetic. Scroll long enough and you’re in a hall of mirrors: deepfakes, AI‑written posts, “authentic” content that may or may not have a human being on the other side of the screen.

Against that backdrop, handing someone a handwritten letter with your actual feelings on the page makes a very different impression. There’s no algorithm, no filter, no invisible server farm in the middle—just your hand, your pen, and the marks you left on that paper. The slight wobble in a line, the way you cross out a word, the pressure of the nib in one sentence and not the next all say, “A real person sat down and wrote this, for you.” In a world where it’s becoming harder to decipher real from fake, that kind of direct, physical, personal message feels more grounded—and more valuable—than ever.

Recommended Retailers in the USA

In these times, it’s become very important to me not just to support small businesses, but to ensure those businesses aren’t backing causes that present harm to people for who they are, who they love, or where they come from.

Here are a few places where you can purchase all your pen/journal/stationery needs, support small companies, and do so with a conscious awareness of the value of everyone around us.

The Toolkit for Musicians and Improvisers

When I’m music journaling, I always have the Toolkit for Composers and Improvisors by my side. It not only gives me prompts to break through musical stalemates, but also reminds me of the many options—and their “recipes”—when I’m looking for different colors in modes and scales.