A Brief But Complete Guide to Fuzz Pedals

Fuzz pedals are a unique part of guitar and bass tone. They come in several circuit families, and the differences from pedal to pedal can be surprisingly dramatic, especially for players just entering the world of fuzz. They are not simply plug‑and‑play devices. Sometimes you may get lucky and everything lines up, but other times you end up scratching your head, wondering why it doesn’t sound the way you imagined. The truth is that it’s rarely a single “wrong” setting or one quick fix; getting great fuzz tones is really about understanding the nuances of the circuit, the amp, and the guitar all working together.

Why Hand‑Tuned Fuzz Still Matters

Simply throwing the required components that make up a fuzz pedal into a casing is not enough to get a desirable tone. Builders who really know the ins and outs of fuzz tune their pedals by ear and meter, matching transistor gain, leakage, and bias for each unit. This is why truly great fuzz pedals are still often made and biased by hand if you want consistent, musical results.

Sure, some companies have tried to automate the process, but the average mass‑produced fuzz rarely gets that last 15–20 percent of fine bias adjustment and transistor selection that transforms a circuit from “works on paper” to “inspires you to play for hours.”

My Early Disappointment with Fuzz

When I first tried a fuzz pedal—a Dunlop Fuzz Face—I was greatly disappointed. I did not know much about fuzz; I bought it because it was marketed as the Jimi Hendrix fuzz, and in the 1990s there were not a lot of easily accessible boutique options.

Plugging the Dunlop Fuzz Face into a Fender reissue Twin Reverb, which I later realized is not a great pairing for classic fuzz, left me confused. The sound was flabby and unresponsive, the tone dull, and while my Strats and Les Pauls were not ideally set up for that combination either, the fuzz was still blaringly bad.

Eventually, I found what felt like the Holy Grail of Strat and Tele pickups and Les Paul humbuckers, and I also found amps that are better suited to fuzz pedals—circuits that break up earlier and do not have the massive clean headroom of a Twin. It still remained, though, that the Dunlop Fuzz Face I owned was a dud, so for a while I assumed I just did not like fuzz at all.

Today, fuzz is my favorite form of gain. I regularly use several types of fuzz and even variations within the same basic circuits, because small changes in parts and bias create entirely different instruments under your fingers.

Major Manufacturers vs Specialists

In general, I almost always prefer handmade pedals to mass‑produced pedals. The attention to detail and carefully chosen, higher‑quality components really matter with fuzz, where transistor gain and leakage can vary wildly even within the same part number. Major manufacturers, in my experience, score the lowest in the fuzz category; many “assembly‑line” fuzzes are technically correct on a schematic but feel uninspiring or harsh in practice.

Plugging into a generic production fuzz is like pulling a shot of beautifully roasted espresso beans and then mixing it with milk that has just started to turn—everything is there on paper, but something is clearly wrong in the delivery. Poor chocolate works the same way: it is either great or disappointing; there is not much middle ground. That is exactly how fuzz feels to me: there may be different circuits and flavors, but a fuzz is either good or bad.

Change of Heart: Discovering the Sun Face

My opinion changed when I tried the Analog Man Sun Face. Mike Piera (Analog Man) builds his fuzzes around carefully selected germanium or silicon transistors and provides detailed information on how to pair them with amps, cables, and guitars. Reading about proper fuzz use—especially why classic Fuzz Face circuits tend to prefer amps that do not have unlimited clean headroom—helped me understand why my Fuzz Face into a Twin Reverb had been such a mismatch.

The Sun Face was recommended by a friend and had a reputation in the scene as a specialist’s pedal. Piera is extremely picky about individual transistor characteristics, especially gain and leakage, and he hand‑biases each unit, which is something most big manufacturers cannot afford to do at scale.

Upon receiving the Analog Man germanium Fuzz Face–style pedal, I was blown away. Even though Fuzz Face circuits generally sound better into amps that are not ultra‑clean, this Sun Face sounded good even into a non ideal amp. That experience proved to me that a properly designed and biased Fuzz Face‑type circuit can still work in less‑than‑ideal amp pairings—and that if I got stuck with a backline Twin I could still get through the gig espeically when I figured out that placing an Effectrode Tube Drive after a fuzz can drastically help with bad backline amps.

Analog Man even offers an additional “Sun Dial” bias knob on Sun Face models, letting you re‑bias the germanium transistors as temperature changes or to deliberately move from smooth sustain to gated, spitty textures. This is a powerful tool in real‑world conditions where stage lights and sun can heat pedals enough to shift their operating points.

Components and Why Transistor Choice Matters

When you look up small pedal builders, you will notice detailed listings of which transistors and parts they use. That is because specific transistor families are a huge part of the voice of classic fuzz circuits: for example, original germanium Fuzz Faces often used Newmarket NKT275 transistors, while some Tone Benders used OC75 or similar germanium types.

Imagine ordering a bagel labeled “cinnamon raisin” but getting something with no cinnamon. A lot of fuzz circuits branded as “Fuzz Face” or “Tone Bender” can be like that: the name is right, but the components, gain ranges, and biasing are nowhere near the classic recipe. Simply labeling a pedal as a Fuzz Face does not guarantee the classic tone people associate with units heard on Hendrix or Gilmour recordings. Many mass manufacturers cut corners on parts selection and use whatever transistors are cheapest or most available that week.

The builders I mention in this article are very picky about every component, especially transistors, which can have significant variances even within the same part number. Each transistor is measured, sorted, and matched to a specific position in the circuit, a process most large manufacturers consider too costly and time‑consuming.

It should be mentioned that the original short “fat‑can” Newmarket NKT275s are effectively gone from normal distribution; what remains is small stashes for boutique pedals or collectors rather than anything that could support true production‑line use. The long, skinny “NKT275” cans that show up all over eBay and in some later pedals are widely considered relabeled or non‑Newmarket parts, with inconsistent specs and often mediocre tone compared to genuine TO‑1 Newmarket transistors. As a result, I would caution that almost all of the eBay “NKT275” listings are fake, rebranded, or at least not the classic Newmarket transistor people associate with vintage Fuzz Faces and early Analogman Sun Faces.

You may be wondering how a Fuzz Face circuit can sound great without the legendary Newmarket NKT275s. The key is that when a builder really understands what to look for in a transistor—and knows intimately what the original circuits sounded and felt like—they can get outstanding results with other parts. In this case, someone like Mike Piera is not just dropping in any random “replacement” transistor; he is using carefully selected, measured transistors that hit the right gain range, leakage, and response for that specific circuit.

On the Analog Man site, you can even choose from different transistor options and gain ranges, which reflects how much thought goes into matching parts rather than chasing one mythical part number. The components absolutely matter, but not always in the simple, marketing‑friendly way of “this exact transistor or nothing.” What truly counts is how those transistors are chosen, tested, and biased in the context of the whole circuit so the pedal behaves like the classic fuzz tones players love.

Beware of “Correct Parts List” Marketing

Even seeing the “right” transistor numbers on a spec sheet is not enough. One must ask whether the builder tested the devices, understands how to bias them, and has a solid sonic reference. A builder may advertise genuine new‑old‑stock NKT275 transistors in a Fuzz Face clone, but if the gain range is wrong or the bias is off, the pedal can still sound thin, splatty, or muddy.

It is the combination of properly measured transistors, good biasing, and the builder’s taste that makes a fuzz great. Taste is critical because the person biasing the pedal can make it sound bad even with the most coveted transistors—just like a chef can ruin great ingredients.

There are many fuzz pedals on the market, and many market their use of NOS components. That is only part of the puzzle. Doing research on builders’ track records, listening to demos with your style of playing, and, yes, considering respected specialists like Analog Man for Fuzz Face‑style tones are all smart steps.

“There are many fuzz pedals on the market, and many market their use of NOS components. That is only part of the puzzle. ”

Builders with Specific Fuzz Specialties

In the fuzz world, builders often have niche strengths. Analog Man is deeply associated with Fuzz Face‑type circuits and is widely regarded as one of the most consistent and musically focused voices for that topology.

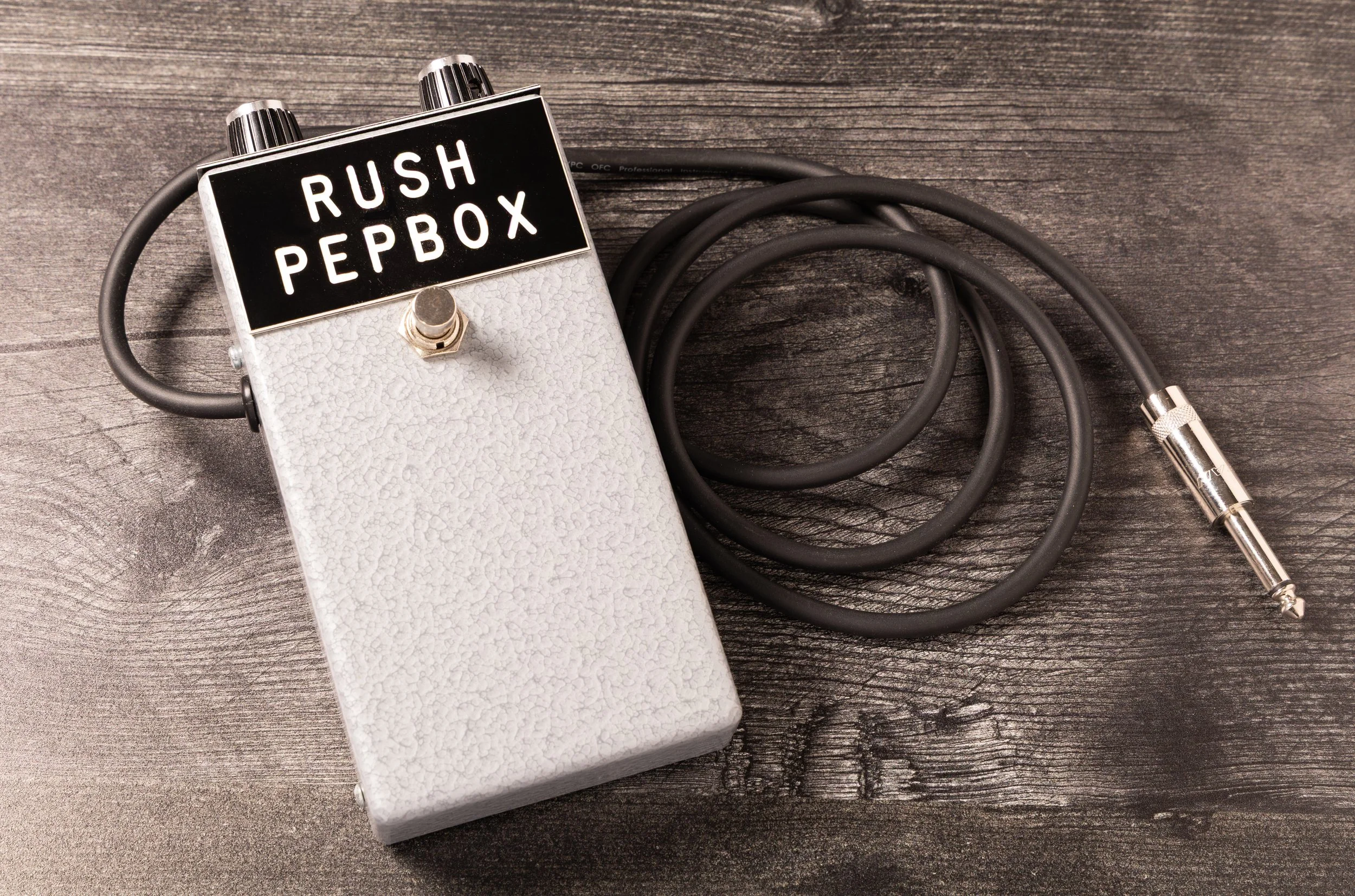

For earlier‑era fuzz, the Rush Pep Box is a standout. The original Pep Box was designed in mid‑1960s London by Pepe Rushand produced by Rush Pep Box; it is closely related in spirit to Maestro‑style early fuzzes and is still being made in authentic form by his family. The modern Pep Box captures those raw, brassy early‑’60s textures that sit between the Maestro FZ‑1A and later British fuzz designs, with a bright, cutting top end and a spitty attack that feels perfect for vintage‑leaning rock and garage tones.

What makes the current Pep Box especially compelling is how directly it connects to that original lineage: Pepe’s daughter Lucy builds them by hand in the UK, using period‑correct parts—including new‑old‑stock germanium transistors—so the response, volume‑cleanup behavior, and slightly temperamental feel are very much in line with the mid‑’60s units. It is less about smooth, modern saturation and more about a living, breathing fuzz that reacts dramatically to your picking and guitar volume, giving players access to the same unruly, characterful sounds that once floated through Soho studios and onto classic ’60s recordings.

Effectrode makes unique tube‑based fuzzes (more on that later) that replace transistor clipping with vacuum tube stages, giving a different compression and harmonic profile than transistor fuzz while remaining in the fuzz family when pushed hard.

Big Muff: Disillusionment and Better Clones

Big Muffs are another area where I was initially disappointed. Many years ago, I bought an Electro‑Harmonix Big Muff Pi and found it unusable, eventually selling it; again, amp pairing and component variability were major factors.

Classic Electro‑Harmonix production often used whatever parts were available, leading to wide variance between supposedly identical Big Muffs. Builders like vick audio (now defunct) made highly regarded Big Muff–style clones by carefully copying favorite historical versions and using tightly spec’d components, resulting in far more consistency.

Wren and Cuff is another company that specializes in Big Muff circuits. They offer specific recreations of well‑known variants (Civil War, Ram’s Head, etc.) and are very picky about component choices and build quality, which is why many players treat them as reference‑grade modern Muffs.

Tone Benders: The Second Fuzz Era

Tone Benders sit in what feels like the second era of fuzz to me, following the Maestro and leading into the Fuzz Face. The original Sola Sound Tone Bender MK1 was developed by Gary Hurst in London and used three germanium transistors; later versions like the MK1.5 and Professional MKII shifted topology and feel. The MK1.5 was a two‑transistor design that strongly influenced the Arbiter Fuzz Face circuit that followed.

MK1 Tone Benders have a unique quack and spitty, gated feel, with a sticky attack that grabs the note quickly and then decays with character. They are also mid‑range‑rich, which lets them cut through a dense band mix without needing to crank the volume excessively.

A famous user of the MK1 Tone Bender is Mick Ronson, whose searing tones on David Bowie’s “Ziggy Stardust”–era material are strongly associated with that pedal. Unfortunately, the Tone Bender MK1 was produced in small numbers and for a short time, so original units are rare and expensive. Many current builders offer MK1‑style fuzzes, but there are significant tonal differences among them.

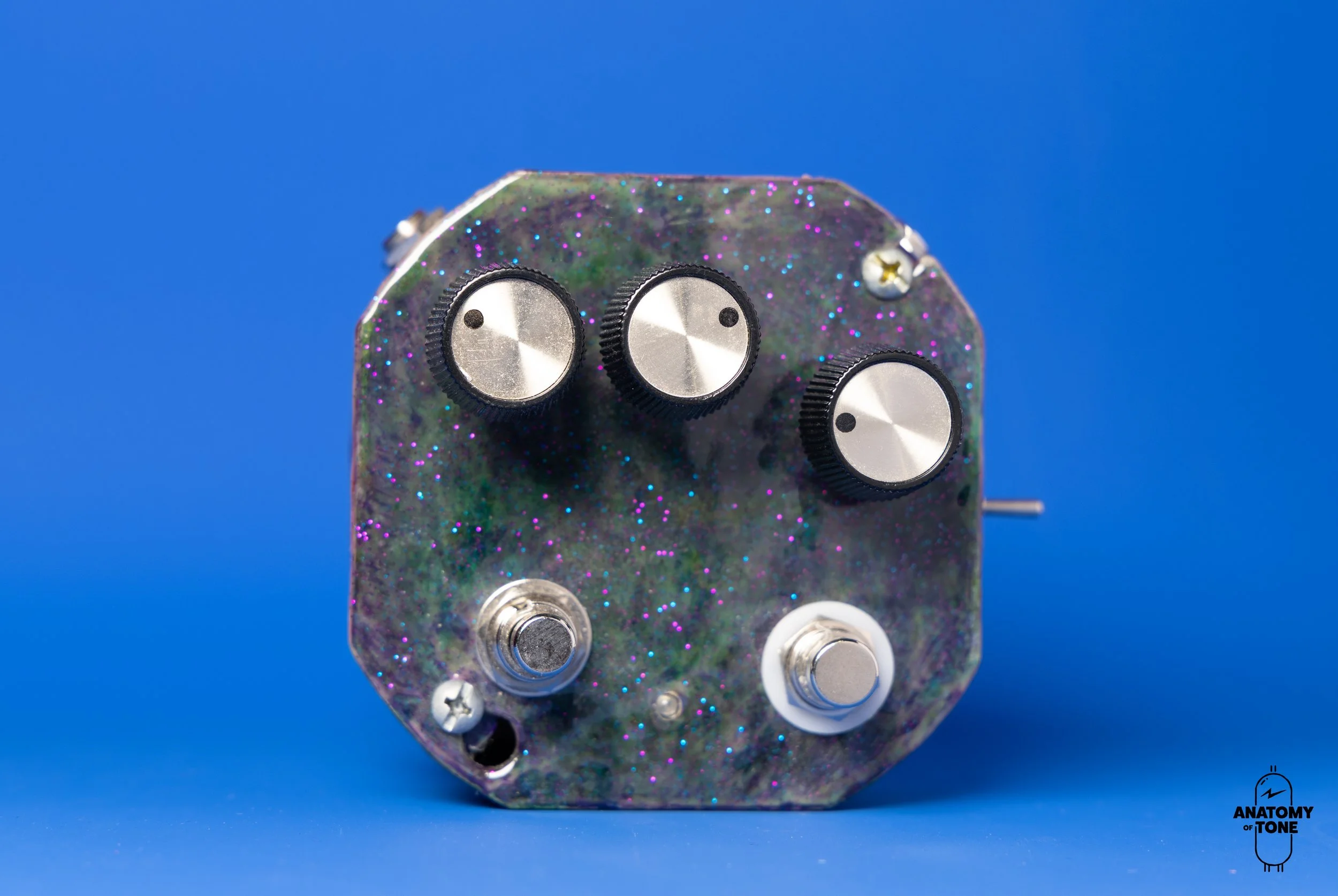

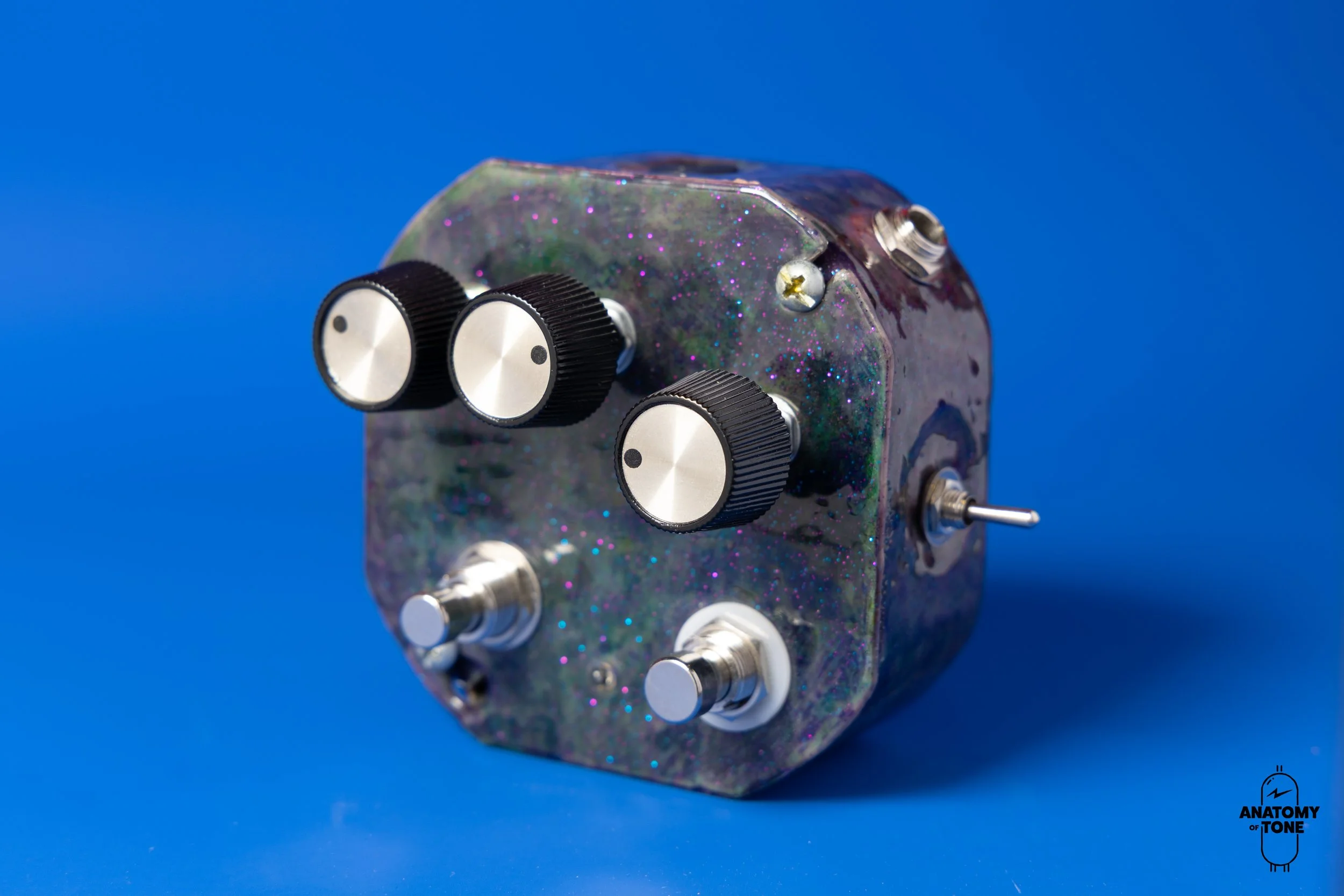

Two of my favorite MK1‑style builders are Seeker Effects and LIC Pedals. The Seeker tends toward a more traditional MK1 voice, though many builders—including Seeker—will tweak the circuit on request. L.C.’s take leans more toward shoegaze‑friendly textures, demonstrating how even a simple three‑transistor circuit can be tuned to different niches.

Although Tone Bender circuits are relatively simple, their tuning radically changes their character. It is similar to how eggs are a simple ingredient, but very few chefs truly master them; biasing and voicing a Tone Bender separates the merely functional from the magical.

Choosing Fuzz by “Family”

When choosing a fuzz, it helps to think in terms of families of tone and response. What kind of recording or gig are you doing? Do you need the fuzz to cut through a dense mix or sit underneath as a thick pillow of sustain?

For dense mixes where cut and brassiness matter, early‑style fuzzes like the Pep Box or Maestro‑inspired designs and mid‑forward Tone Benders tend to slice through more effectively than a Fuzz Face or Big Muff.

In a trio or more open arrangement, a Fuzz Face or Big Muff can work beautifully, as they are less brassy and bold and can fill out a wider range of frequencies without stepping on other instruments.

Volume‑Knob Interaction and Cleanup

One of the most important aspects of fuzz is how it responds to the guitar’s volume knob. Some circuits, especially germanium Fuzz Faces, are famously interactive: rolling back the volume can morph full‑on fuzz into chimey, lightly compressed clean tones. Jimi Hendrix, for example, often achieved his articulate cleans by running a germanium Fuzz Face and simply lowering his guitar’s volume rather than switching pedals.

Other fuzzes are less cooperative. Early Maestro‑style circuits and some Tone Benders have narrower “sweet spots” on the volume knob, where rolling back just a small amount—say from 10 to 9.5—yields a slightly less compressed, more percussive tone without fully cleaning up.

Volume‑Knob‑Friendly Circuits

The ultimate volume‑knob‑friendly fuzz is the germanium‑based Fuzz Face. Original Arbiter Fuzz Faces used two Newmarket NKT275 germanium transistors biased so that rolling back the guitar volume gradually reduces clipping and treble roll‑off, producing sparkly, touch‑sensitive cleans. Silicon Fuzz Faces can still clean up, but the taper is less smooth and the top‑end character is different, so they generally do not deliver the same “magic” cleanup.

The Pep Box and Maestro FZ‑1A have their own volume‑cleanup behavior. The FZ‑1A, a refinement of the original FZ‑1 designed by Glenn Snoddy and Revis Hobbs for Gibson’s Maestro brand, used three germanium transistors and tends to respond best to just a click or two of volume rollback, giving a punchier, less compressed tone while retaining some grit. Many players keep the guitar slightly below 10 with these early circuits to sit in that sweet spot.

Tone Benders, especially MK1 and MKII types, often respond best to minimal volume reduction as well. Dropping a Strat’s volume from 10 to around 9.5 can yield a special quack for rhythm guitar, with slightly exaggerated attack and less compression, while turning down further can make the pedal feel choked or anemic.

Why Germanium Feels Alive (and finicky)

All of the classic fuzzes mentioned—Maestro FZ‑1/FZ‑1A, Tone Bender MK1/MKII, Fuzz Face, Pep Box—were originally germanium‑based. Germanium transistors have lower forward voltage and different leakage characteristics than silicon, which contributes to their soft clipping and responsive cleanup but also makes them temperature‑sensitive.

If a germanium fuzz gets too hot, its bias points shift; the pedal can become noisy, gated, or thin. This is why builders like Analog Man offer external bias controls such as the Sun Dial, allowing players to re‑center the bias as the pedal heats or cools, and why many germanium fuzzes simply sound better in cooler rooms or shaded stages.

There are a few modern builders who have worked hard to make germanium‑style fuzz less temperature‑dependent. Designs like Benson’s temperature‑compensated germanium fuzz use additional circuitry to stabilize bias so that stage heat does not ruin the sound mid‑set.

Octave Fuzz

Octave fuzz sits in its own little corner of the fuzz universe, and the Tycobrahe Octavia is still the reference point. Designed from Roger Mayer’s original Octavia concept and released commercially in the early ’70s, the Tycobrahe version delivers that unmistakable upper‑octave bloom Jimi fans associate with leads above the 12th fret: a mix of saturated fuzz, doubled pitch, and subtle ring‑mod style grind that gets more intense as you move up the neck. The same basic idea underpins other octave fuzz classics like the Foxx Tone Machine, which pairs a thick, gnarly fuzz with a switchable octave‑up stage so you can go from chewy, sustaining riffs to screaming, octave‑lifted lines on demand.

Modern designs like the JAM Pedals Octaurus take that Octavia lineage and make it more playable across the whole fretboard. JAM’s goal with the Octaurus is a clearer, more consistent octave effect that still feels analog and wild, but without having to “hunt” for a tiny sweet spot high on the neck. Between the voicing toggle (from mid‑scooped, industrial fuzz to fuller, lead‑friendly tones) and the clipping options, it reads like a thoughtful nod to the classic Octavia idea rather than a straight Foxx Tone Machine clone: a modern octave fuzz that channels the spirit of those late‑’60s/early‑’70s units while giving players finer control over how much octave, compression, and aggression they want

Silicon: Strengths and Trade‑Offs

Silicon transistors are more stable, consistent, and cheaper to manufacture, and they are less sensitive to temperature and pedal‑board placement. Many builders—including the companies behind later Fuzz Face and Maestro variants—switched to silicon for reliability and cost reasons.

Tonally, silicon fuzzes tend to have more gain, tighter low end, and brighter top end. They can be pretty aggressive.. They do not usually clean up as gracefully with the guitar volume, but they excel at high‑gain lead sounds, stacked with overdrive, or into already‑driven amps. The Electro‑Harmonix Big Muff, for instance, is a silicon‑based design that sits between fuzz and distortion, using multiple transistor stages and diode clipping to produce massive sustain and thick saturation.

The silicon Fuzz Face, which can be heard on Pink Floyd’s “Dark Side of the Moon,” sounds noticeably different than its germanium ancestor: more bass‑heavy, and more mid scooped , with a slightly less nuanced cleanup.

Fuzz vs Distortion

Fuzz and distortion differ not only in feel but also in topology. Typical distortion circuits often reduce low frequencies before the clipping stage and then add bass back after clipping, which helps maintain tightness and clarity at high gain. Classic fuzz circuits, by contrast, tend to clip the full‑range signal, which is why they can feel huge and unruly and why they respond so strongly to pickups, cables, and amp voicing.

This is why something like a Big Muff—though often marketed as a distortion or “sustainer”—behaves and feels like a very saturated silicon fuzz more than a classic distortion box.

Batteries, Power, and Sag

Power matters for fuzz. Many vintage‑style fuzz pedals were designed around carbon‑zinc 9‑volt batteries rather than modern alkaline cells or regulated power supplies, and their bias points assume the slightly lower and sagging voltage those older batteries provide.

For that reason, many players prefer to run classic fuzzes on batteries, and some even seek cheap low‑output cells to emulate vintage conditions; lower voltage can subtly soften attack and change the clipping behavior, especially in germanium circuits. Some modern fuzzes run exclusively on DC jacks and can sound great, but when the circuit is a faithful vintage design, using a battery often gets you closer to the intended feel.

Modern creative fuzz designs

Beyond classic clones, there are builders pushing fuzz into new territory. Death By Audio’s Fuzz War and Evil Filter, take a high‑gain fuzz engine and slam it into an extreme multimode filter built around a repurposed medical‑grade IC, with high‑pass, band‑pass, and low‑pass modes, expression/CV control, and resonance ranges that go from subtle tone‑shaping to screaming self‑oscillation. At their wildest settings, these designs produce upper and lower octave artifacts, wavefolded attack envelopes, and grinding, ring‑mod‑like textures that feel far closer to modular synth territory than to a vintage Fuzz Face or Tone Bender.

ZVEX’s Fuzz Factory comes from a different angle but ends up in similarly anarchic territory, starting with a Fuzz Face‑style core and layering on five highly interactive controls—Volume, Gate, Compress, Drive, and Stability—that never behave in a neat, one‑knob‑per‑function way. Small changes to the Gate or Stab controls can send the circuit from thick, sustaining fuzz into choked, velcro‑like gating, radio‑tuning squeals, or full self‑oscillation, which players can “play” with the guitar’s volume and pickup selector. For many experimental guitarists and noise artists, the appeal of pedals like the Evil Filter and Fuzz Factory is not just their gain level, but the sense that the circuit is barely under control—an instrument in its own right rather than a polite tone enhancer.

These modern designs show that while the fundamental idea of fuzz dates back to the early ’60s—beginning with Glenn Snoddy’s Maestro FZ‑1 and early British pedals like the Pep Box and Tone Bender—the palette is far from exhausted.

Tube Fuzz

Effectrode’s Mercury Tube Fuzz is a true vacuum‑tube fuzz built around a space‑grade subminiature triode and NOS germanium diodes, delivering a smooth, glassy response that stays controllable from edge‑of‑breakup dirt to thick, sustaining fuzz as you ride your guitar’s volume. The simple Fuzz and Volume controls hide a wide gain range, moving from chewy overdrive and distortion that plays nicely with Fender, Vox, or Marshall‑style amps to roaring, amp‑like compression that still keeps chords and double‑stops intelligible instead of collapsing into mush.

A rear‑panel Heat switch starves the second tube stage, tightening the attack and shifting the character from rich and hi‑fi to snarlier, grainier, almost transistor‑like splatter, effectively giving you two fuzz personalities in one box with a spectrum of in‑between tones shaped by internal trims. Built with a fully discrete class‑A signal path, audiophile components, low‑noise ground‑plane construction, and silent true‑bypass switching, the Mercury is not chasing a Fuzz Face, Tone Bender, or Muff clone; it is a modern, highly expressive tube fuzz that still feels instantly musical under the fingers.

Vintage Oddities

The Speebtone Harmonic Jerkulator Fuzz is one of those rare circuits that really does feel like its own branch of the fuzz family tree rather than yet another spin on a Fuzz Face, Tone Bender, or Muff. Inspired by the obscure Interfax Harmonic Percolator and filtered through builder Steve’s tweaks, it keeps the Percolator’s asymmetrical, harmonically rich clipping but leans hard into the sensation of amp sag—notes hit with a sharp transient and then almost “breathe” as the level ducks and swells, like a cranked tweed Fender being pushed past its comfort zone.

Instead of a traditional gain control, the fuzz is essentially maxed, with output level handled by a volume knob while a voltage‑starve “magic knob” becomes the real character control, introducing that squishy, collapsing, tube‑like response as you dial the supply down. A feedback control then lets you feed the signal back into the input path, ranging from glitchy stutters at low settings to self‑oscillating noise‑generator territory when wide open, which makes the Speebtone Jerkulator as much an experimental sound‑design tool as it is a musical, sag‑soaked fuzz for more conventional riffs and lines.

What’s the Deal with Bright Caps?

A bright cap is a small capacitor wired so that only the higher‑frequency part of your signal can slip around the resistance of the volume control, while the rest of the signal still has to go through the full pot. In other words, the cap gives the treble a shortcut from the input side of the pot to the output side.

Bright caps are one of those tiny amp parts that quietly decide whether your fuzz sounds glorious or like a can of angry bees. In simple terms, a bright cap is a small capacitor that lets high frequencies “step around” part of the volume or gain control. At lower amp volume settings, that bypass gives you extra top end—more cut, more glass, more presence. On a clean tone, especially with single coils, that can feel lively and articulate. With a fuzz pedal in front, it can push the sound right over the edge into harsh, spitty territory.

At lower volume settings, the pot is adding a lot of resistance to the main signal path, so most of the lows and mids are being turned down. The cap, however, is still letting some of the highs bypass that resistance, so the highs are reduced less than everything else. That’s why the amp feels extra bright or glassy when the volume is low: in relative terms, the treble has “skipped the line” and arrived at the next stage louder than the rest of the spectrum.

As you turn the volume up closer to max, the pot’s resistance drops and more of the full‑range signal is allowed through normally, so there’s no longer a big difference between what the cap is passing and what the pot is letting through. At that point the bright cap basically goes out of play and the amp’s frequency balance evens out. That’s also why players often say the bright cap is a big deal at bedroom levels and almost a non‑issue when the amp is dimed or at stage volume.

This is why fuzz pedals often behave so differently as you turn an amp up. At low volumes, the bright cap is doing a lot of work, emphasizing upper mids and treble while the power section is still clean and stiff. A fuzz pedal already throws a pile of high‑frequency content and odd harmonics at the amp, so the bright cap effectively spotlights the ugliest part of the fuzz. You step on the switch, and suddenly your tone is thinner, fizzier, and more ice‑picky than the bypass sound, even though the basic EQ on the amp hasn’t moved. As you raise the volume and the amp heads toward breakup, the bright cap’s influence fades, and the power section starts to compress and “swallow” that extra fizz, which is why the same fuzz often sounds way better loud than it did at home.

A lot of classic circuits are wired this way. Black panel and Silver panel Fender designs commonly use a bright cap on the bright channel, sometimes tied to a bright switch and sometimes hard-wired into the circuit. The ’65 Deluxe Reverb reissue, for example, has a bright cap on the Vibrato/bright channel that many players end up clipping or turning down because it can be brutally sharp with pedals.

Tweed-style Bassman circuits use a bright cap on the bright channel’s volume pot, which is a big part of why that input feels so much more cutting than the normal channel at the same settings.

Marshall lead circuits, like the 2203/2204 family, lean on fairly large bright caps across their preamp volume controls, which is why they can sound razor‑edged and aggressive at low master settings.

Vox‑type amps with a Top Boost channel often do a similar thing, baking in an extra slice of treble that’s very noticeable until the amp is really cooking.

From a fuzz perspective, all of this translates to a few very predictable headaches. It becomes hard to find a single amp setting that flatters both the bypass tone and the fuzz tone. You get a clean or edge‑of‑breakup sound that feels nice and balanced, then you hit the fuzz, and the whole top end jumps forward in a way that’s not musical anymore. Fuzz circuits that are designed to clean up from the guitar’s volume control become less forgiving, because every little change at the guitar is now being fed into a front end that is already hyping the highs. What should be a smooth transition from woolly to glassy turns into a narrow, touchy range between “mud” and “splatter.”

The good news is that bright caps are not a death sentence for fuzz, but they do force some different habits. The obvious move is to defeat the bright function if your amp gives you a switch for it and let the standard treble control handle top end. Running the amp at least to the edge of breakup helps enormously; once the power section is doing some of the clipping and compression, the bright cap’s worst exaggerations get smoothed out and the fuzz feels thicker and more integrated with the amp.

On the guitar side, working the volume and tone controls is not optional—it’s the whole point. Rolling the volume back a touch and shaving just a bit of tone can bring a bright-cap-equipped amp into the sweet spot where the fuzz still cuts, but the ice pick is gone. And if you absolutely love the amp but always hate it with fuzz, talking to a tech about reducing or removing the bright cap is often a small, reversible tweak that makes the amp far more fuzz‑friendly without ruining what you like about it clean.

Observations when testing fuzz pedals for the examples:

One reason fuzz doesn’t always work with amps that have a lot of headroom is that fuzz tends to sound fuller when the front end of the amp is being pushed into saturation. When the amp stays very clean and doesn’t compress, the fuzz can turn shrill, especially if you raise the fuzz level high enough to feel exciting. That often puts the engaged level in conflict with the bypassed sound of the pedal, so you end up choosing between great fuzz tone and a usable clean level.

Decay is also a big part of fuzz. As the note dies away, the sound moves through several different “colors,” and that behavior changes from pedal to pedal. Each fuzz has its own built‑in attack character, EQ curve, and sustain profile, which is why two fuzz circuits can feel completely different even with similar settings.

For these examples, a Gibson SG Custom with Gemini Mercury One pickups was used into a Marshall SV20 Plexi. It’s not the most traditional pairing for running four or five fuzz pedals, but it has been a really inspiring combination lately. With so many fuzz demos built around Strat‑style guitars, this setup adds a bit of variety, and the Marshall was set just on the edge of breakup.

Audio Examples:

In these examples, I played the same material: a power chord ringing out, a riff with the bridge pickup and neck pickup, and then a solo with both bridge and neck pickups. It was the simplest way to show each fuzz’s character. There is a lot more variety available with some of these pedals, like the Zvex Fuzz Factory, which can drastically shift its vibe, and with the exception of the Rush Pep Box I didn’t go deep into rolling back the guitar’s volume knob.

Rush Amps Pep Box

The Pep Box has an almost oboe‑like tonal quality, more nasal than most other fuzz pedals. That nasal quality shifts when you roll the volume knob back, giving you a brighter tone with more attack.

Seeker MKI Tonebender

The MKI Tonebenders have the most attack and can really cut through a mix. They have a cool spitty quality and an aggressive feel, with a sticky way the fuzz grabs the note that I really like.

MKII Tonebender

The MKII Tonebender still has plenty of attack and a nice upper‑midrange presence. It is not as spitty as the MKI; the sound is more refined, but it still has that sticky feel and can cut through a mix.

Analog Man Sunface Germanium

The Sunface, based on the original Dallas Arbiter Fuzz Face circuit, has a slightly softer attack and less midrange than the Tonebenders and the Pep Box. It doesn’t have that spitty, gated sound and is smoother, with longer sustain before the note finally drops away.

Analog Man Sunface Silicon

The Silicon Sun Face, the silicon version of the original Dallas Arbiter Fuzz Face, is more scooped and has even less attack. Its character is not as wild; germanium fuzz pedals always sound a bit dangerous to me, while the silicon Sun Face is more predictable and works better in varying temperature environments.

FSC Fuzz

FSC designed this pedal to have a germanium‑style response even though it actually uses silicon. You get that germanium‑like attack with silicon reliability. They also added options for a midrange boost either before or after the fuzz, and it’s wild how much that changes the sound and the way the fuzz reacts.

Jam Octaurus

I much prefer Octavia‑style octave fuzz to the Foxx circuit. The JAM Pedals version of the Octavia, with a few additional and welcome features, really excites the guitar signal without sounding overly synthy.

Vick Audio Ram’s Head

This pedal, which is no longer made, is essentially a 1972 Electro‑Harmonix Big Muff. Big Muffs have more sustain, a noticeably scooped EQ, and a compressed attack, and they can take on an almost pad‑like quality on chords because of that softer, smeared front edge.

Zvex Fuzz Factory

The Fuzz Factory is a germanium fuzz, but it isn’t a recreation of a vintage circuit. Zvex leans into the weird side of fuzz—self‑oscillation, extreme gating, and unstable textures—so you can get anything from zipper‑like effects to synth‑like attack to chaotic oscillation. It’s hard to show everything this pedal can do, so here I chose a fairly basic sound just to give a broad sense of its core tone.

Effectrode Mercury

The Effectrode Mercury is a tube fuzz pedal, and there really isn’t a direct comparison for it. It sounds like a fuzz, but not like one that has existed before: there’s a solid attack, rich midrange, and plenty of presence. One of its standout traits is how well it handles full chords, keeping individual notes clear instead of collapsing into mush, and it also cleans up into a unique, lightly overdriven sound that I’m a big fan of.

Death by Audio Evil Filter

Death by Audio is known for walking the less‑traveled path, building unusual and creative pedals that are especially at home in noise‑leaning music. On the Evil Filter, there’s a really interesting bloom as a note sustains—almost a sag‑like feel, but with a defined initial attack—and the fuzz tone has a wonderfully ragged edge that keeps it from ever sounding polite.

Historical Context

The first widely marketed fuzz pedal was the Maestro FZ-1 Fuzz-Tone, designed by recording engineer Glenn Snoddy with engineer Revis V. Hobbs for Gibson in 1962, using a three–germanium-transistor circuit. Biasing and transistor choice—especially in classic germanium and silicon fuzz designs—are the main reasons two pedals with the same name can feel completely different under the fingers.

Who really invented fuzz?

The sound that became fuzz started as an accident: Nashville engineer Glenn Snoddy captured a broken mixer channel on Grady Martin’s bass track for Marty Robbins’ “Don’t Worry” (1960) and liked the shredded, buzzy tone enough to chase it on purpose. Snoddy then prototyped a three-germanium-transistor fuzztone circuit using 2N270 transistors and took it to Gibson, where he and engineer Revis V. Hobbs refined it into the production Maestro FZ‑1 Fuzz‑Tone released in 1962.

The FZ‑1 was marketed as a way for bass or guitar to imitate baritone sax or trombone, and the first production run of about 5,000 units initially sold poorly—Gibson reportedly made only three more units in 1963 and none in 1964. Everything changed when Keith Richards used an FZ‑1 on “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” in 1965, turning fuzz from a novelty into a must‑have sound almost overnight.

Germanium vs silicon: why fuzz feels alive

Most classic fuzz pedals are just a handful of transistors biased to misbehave, but the choice and biasing of those transistors completely changes attack, clean‑up, and how the pedal sits in a mix.

Germanium devices (e.g., early 2N and Mullard types) clip softer, with lower typical gain (often around 70–120 hFE), limited bandwidth, and strong interaction with guitar volume, so they clean up into chewy, almost overdrive‑like textures.

Silicon transistors can have gain factors 3–4× higher, more treble, and much tighter, more aggressive clipping, so they’re brighter, louder, and more stable across temperature and power conditions—but usually clean up more glassy and less “woody.”

Germanium fuzz circuits are notoriously temperature‑sensitive: bias points drift as the stage warms up, which is why the same pedal can sound magic in a cool studio and flubby on a hot stage. Silicon fuzzes were embraced in later designs not only for lower cost but because their bias is easier to set and keep in the sweet spot.

How biasing actually changes fuzz tone

Bias in a fuzz is essentially where the transistor “idles” on its transfer curve, and tiny changes here dramatically affect compression, note bloom, and noise. In classic two‑transistor topologies, guitarists often listen for a bias voltage on the last transistor’s collector in the ballpark of half the supply, but the “right” value is really the spot where the waveform clips symmetrically enough to sound big yet asymmetric enough to stay expressive.

When the fuzz is under‑biased (collector voltage too low on the last stage), you tend to get:

Gated, sputtery decay where notes choke off abruptly

Very touch‑sensitive response that can feel broken or “velcro‑like.”

Leaner bass and a sense that chords get pulled apart rather than smeared

When the fuzz is over‑biased (collector voltage too high):

The sound becomes more open and less compressed, but can lose sustain

The clipping can start to feel harsh and stiff, especially with silicon

You hear more string and pick, less of the classic woolly smear

Sitting bias near the “middle” of the transistor’s swing generally gives maximum sustain and the archetypal singing fuzz, but the magic for many players is slightly off‑center: a little starved for gated textures, or a bit hotter for sharper attack. This is why bias controls on modern boutique fuzzes are more than gimmicks; they effectively let you slide between spitty, dying‑battery chaos and smooth, violin‑like lead sounds.

Classic fuzz models, guts, and inventors

Below is some information on the inventors and details of the original fuzz designs.

Maestro FZ‑1 / FZ‑1A

Inventors / makers: Glenn Snoddy (concept) and Revis V. Hobbs (circuit), manufactured and marketed by Gibson under the Maestro brand.

Transistors: Three germanium transistors in series; early prototypes used 2N270 germaniums, with production units using similar transistors in a three‑stage configuration powered by two 1.5 V batteries.

Biasing behavior: Multi‑stage design with fixed bias points tuned for the buzzy, brass‑like “horn” effect Gibson was chasing, which produces tight, relatively stiff attack and not a lot of classic clean‑up via the guitar’s volume knob.

Notable users: Keith Richards on “Satisfaction,” Grady Martin (whose accident inspired it), and a wave of mid‑’60s session players who wanted that exact single‑note, compressed rasp.

Sola Sound Tone Bender family

The Tone Bender line from Macari’s/Sola Sound in London is really a family of different circuits, all fuzz, all nasty, but with different transistor types and bias goals.

Inventors / makers: Developed in mid‑’60s London by Gary Hurst in collaboration with the Macari family (Sola Sound), with multiple versions (MKI, MK1.5, Professional MKII, etc.).

Transistors and flavor:

Early MKI: three germanium transistors, heavily influenced by the Maestro architecture but biased hotter for more sustain and thickness.

MK1.5 and Professional MKII: two‑ and three‑transistor germanium designs closer to what became the Fuzz Face topology, famous for their fat mids and compressed, violin‑like leads.

Biasing notes: Tone Benders are a clinic in how germanium bias shifts their personality—slightly under‑biased MKI/MKII units get that snarling, ripping decay, while better‑centered examples sustain like an overdriven amp pushed over the edge.

Notable users: Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, Mick Ronson, Pete Townshend, Ronnie Wood (early Birds), and even jazz guitarist Terje Rypdal on some gloriously un‑jazz‑like sounds.

Arbiter Fuzz Face

Inventor / maker: Introduced by Ivor Arbiter’s company Arbiter Electronics in London around late 1966 as their entry into the fuzz market.

Transistors:

Earliest Fuzz Faces: two‑transistor germanium designs using Newmarket transistors (commonly NKT275), low to medium gain, warm, and extremely volume‑sensitive.

Later versions: silicon transistors swapped in for more gain, edge, and stability; modern Fuzz Faces exist in both germanium and silicon lines.

Biasing & feel: The classic two‑transistor feedback pair is extremely bias‑sensitive; a change of a few tenths of a volt on the output transistor can move the pedal from fizzy and gated to huge, glassy, and open.

Notable users: Jimi Hendrix and Leigh Stephens (Blue Cheer) were among the earliest Fuzz Face users; germanium versions are linked to Hendrix’s warmer tones, while silicon versions are associated with his brighter, high‑gain sounds.

Electro‑Harmonix Big Muff Pi (for contrast)

Inventor / maker: Designed in late ’60s New York by Mike Matthews and Bob Myer for Electro‑Harmonix.

Transistors: Multiple cascaded silicon transistor stages driving diode clipping, which yields the massive sustain and scooped mids associated with Big Muff sounds.

Biasing & response: Bias is generally set for high headroom and heavy clipping in later stages rather than the marginal, starved behavior of classic germanium fuzzes, which is why Big Muffs feel smoother and less interactive with guitar volume.

Notable users: David Gilmour, countless ’90s alternative and shoegaze players, and modern heavy acts looking for saturated, sustaining walls of fuzz.

Entertaining Fuzz Trivia

The original FZ‑1 production run was such a flop that Gibson essentially abandoned it until “Satisfaction” accidentally turned their dead stock into gold; demand spiked only after the record hit.

English tech Roger Mayer was building custom fuzz boxes for Jimmy Page in London even before commercial British fuzz boxes were widely available, reportedly drawing on ideas similar to the FZ‑1 but with locally available Mullard germanium transistors.

Many legendary fuzz tones are literally the result of parts drift: because germanium devices vary wildly, two “identical” vintage pedals can sound nothing alike, which is why fuzz collectors obsess over date codes and transistor batches.

Some of the first marketing copy for fuzz tones tried to sell them as brass‑section emulators rather than distortion devices—essentially pretending the pedal was a horn player in a box